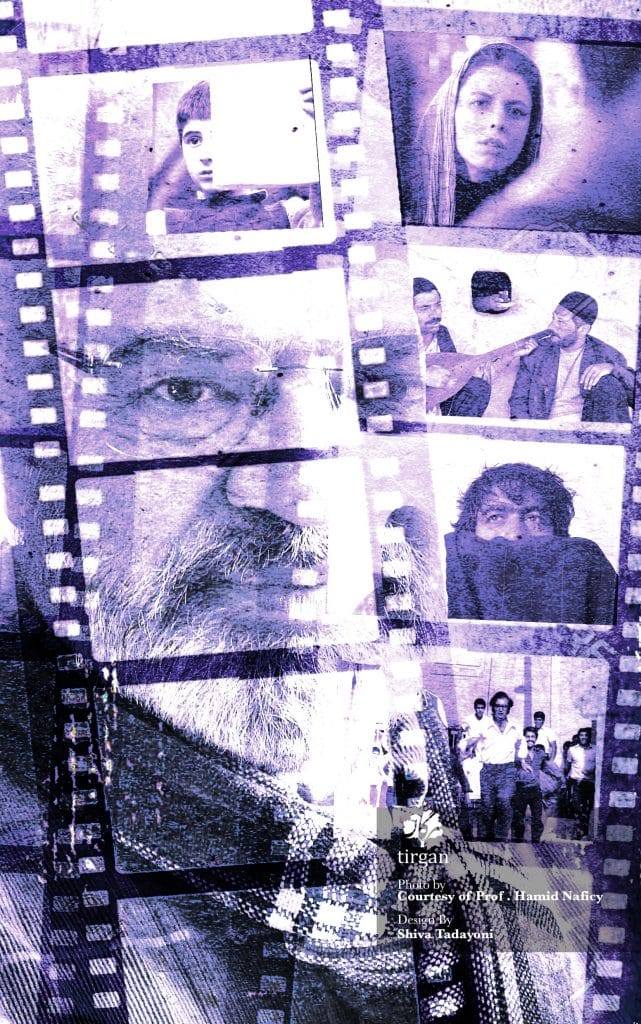

Hamid Naficy literally wrote the book – several books actually – on Iranian cinema. As a scholar of cultural studies (NorthWestern University) his work has focused on questions of identity, diaspora, and cultural production. We caught up with Naficy while he was in Toronto to give a talk at TIFF’s “I for Iran” series.

In your analysis of Iranian films, you’ve always maintained a focus on questions of identity in the context of migration. In the early 1990s you discussed exile and “exilic culture” among Iranian-Americans, and more recently you’ve offered the notion of “accented cinema”. What do you mean by this, and do you think that nostalgia for “homeland” continues to be a major trend in Iranian films produced outside of Iran?

I think we have to distinguish between the different phases of Iranian immigration. I think the first wave of Iranians left Iran in the early1960s, and were primarily students. They formed the largest foreign student body of the US; it was massive, something around 15-16,000…But those Iranian students of the 1960s were temporarily abroad. I think it is the same in Canada and other places where Iranians went to study. The first real wave of immigration began with the revolution (1979), and the majority of those people were ‘well-to-do’. They feared that they would loose their wealth and status in society. There were also religious minorities—Armenians, Jews, and other people—and entertainers, artists, actors, musicians and so on. So that group produced their own kind of film and culture, which is different from subsequent groups. [They] were primarily in exile. Many were refugees and couldn’t go back, neither could the exiles…because of their politics. And yet, they harbored a desire to return. In fact, exile in many ways—as I showed in my book The Making of Exile Cultures, focusing on Iranian TV and cinema in Los Angeles—strengthened their desire to return. [It’s apparent] in a lot of music videos, plays, and films. They exhibited sorrow and anger about the impossibility of going back. Therefore, they began to…represent Iran in a very idealistic and pre-Islamic way. If you look at the logo’s of the television shows of 1980’s, the majority referred to pre-Islamic Iran: Persepolis (takhte jamshid), landscapes of Iran representing permanence, and no reference to contemporary times or to today’s Islamic Republic. These were ways of suppressing the present in order to mobilize the ancient glory of the country. The films…made during this period, were very political and anti-government of Iran. Then two things happened. [First], those who were in exile gradually softened as they had children here, and as their children went to school here, and so forth. They became acculturated. On the other hand, new groups of immigrants came. These were people who were running away from the [Iran-Iraq] war (1980-1988). By class and capital, they were very different from the first wave. Often times, these were middle class or lower. So in the same way Iranian filmmakers…evolved from being exiles to gradually becoming a diasporic population. “Diasporic” in the sense that instead of having a binary relationship between here and Iran—the present and the past—they developed relationships horizontally with other Iranian groups across the world. Those in New York contacted with those in LA, those in LA connected with those in Toronto…Paris and Amsterdam and so forth. So horizontal populations of Iranians began to speak with each other newspapers, TV programs, music. This diasporic consciousness also resulted in less political films. It resulted in film festivals that featured not just films made in L.A., but made in different places; like the one here in Canada… That exclusionary focus on Iran has subsided, I think. Some Iranian filmmakers became ‘ethnic’ filmmakers: making films about Iranian community in the different places they were. [This was] a new category because Iranians had, for a long time, avoided identifying themselves because of hostage crisis, the Islamic government…So they eventually began to come out as ‘Iranian’. In fact, I think a show like Shahs of Sunset was a big push for Iranians to come as Iranians; and as ‘Persians’ because they [still] want to disassociate themselves from the Islamic Republic and identify with a romantic past. That’s how identity has been a moving category amongst Iranian filmmakers and Iranians more generally.

In your recent work on the social history of Iranian cinema you have focused on the increasing role of women in recent Iranian cinema. Can you elaborate on this? What are some of the obstacles that women continue to face the Iranian film industry (whether domestically or internationally)?

Yes! The very first act of censorship in [modern Iranian] history occurred in 1904 over movies showing unveiled women. This was before the Constitutional Revolution (1905-1907). Sheikh Fazlollah Nuri (a prominent cleric) hears that a cinema is showing unveiled women on the screen, and puts out a fatwa. Within a month, this cinema is closed…Since then, Iranian women on the screen and Iranian women in the movie houses have been controversial. Each regime in Iran has used women for its own ends. When Rezā Shāh came to power (1925) his government asked women to remove the veil. When they didn’t, he simply banned the veil (1936). When the Khomeini government came to power (1980), it forced women to wear it. So women have always been used as an instrument of state policy. As a result, their position in society and cultural industries has always been precarious…Before the revolution, only one feature film was made by a woman and after the revolution we had thousand of women who were making feature films. And not only that, there are women in other areas as well: there are women producers and editors. But some parts of film industry are still very male dominated, like working the camera.

In what ways have the criteria of cinematic “quality” shifted in recent years in Iranian cinema? Do you see Iranian cinema as being in decline or progressing?

Well, like before the revolution, post-revolution Iranian film is diverse. There are at least a couple—if not more—parallel cinemas that are going on. Before the revolution you had the ‘Film Farsi’ and the ‘New Wave’. After the revolution you had the war cinema—naturally a draw given the circumstances—and you had Art Cinema led by pre-revolution New Wave directors (Beyzai, Mehrjui, Kiarostami…). They were important in the revitalization of cinema. At the same time you had the parallel cinema of more popular films made by the younger generation of post-revolution directors. But it was this [earlier] generation of filmmakers—I’d call them the “master filmmakers”—who put Iranian cinema following the revolution on the world stage. Post-revolution filmmakers–like Makhmalbaaf, Majidi, Panahi—produced a certain kind of film. These were generally narrative, fictional stories in a conventional way. But a new generation now is rising. They are not following the aesthetics of the reflexive cinema or art cinema of the past. They’re experimenting with techniques, and in dialougue with world cinema and other cinema. They watch a lot of films. Shahram Mokri, for example, made this audacious single-shot film. It’s very complicated! It requires a lot of planning. And yet, he uses Kalari, a well-known and seasoned cinematographer who then relies on his for support to shoot this. …Just consider the ingenuity here, it must be very hard for an older person like Kalari to hold the camera for 137 minutes while moving around all over the place. “Didn’t you get tired?” I asked him. He said that we would hand the camera to his son every 20 minutes, while it’s rolling! So this kind of thin shows confidence in filmmaking among the new generation. So I’m optimistic. I’m also optimistic about the use of new and more accessible technology, like the stuff that Jafar Panahi is doing. And there is all of the filmmaking that evolved out of the Green Movement following the [2009] elections. People are marrying the digital camera to the Internet. They don’t need any money, they don’t need any distributors. They shoot, edit, and put in online. So it’s a whole new world.

I want to discuss contemporary film festivals. Some Iranian film critics have suggested that TIFF’s selection is pretty much the same as that of the 2014 Fribourg International Film Festival (Switzerland) last year. I’m wondering if you’ve thought about this. What could be the role of Iranian ‘cinephiles’ in assisting film festivals organize a better program for Iranian cinema?

Well the film organizer told me that the principal of selection was asking several Iranian directors to name their ‘top-ten’ films. That certainly is one way to do it. I should also say that any selection will have its critics…I think that the selection process would’ve improved if they had embedded the films they’ve already chosen within the social context of Iranian cinema…there are no genre movies; no ‘film-farsi’, or war movies. But even the films that they’ chose could’ve been put in better context by calling them ‘New Wave’ cinema, for example, in order to highlight their stylistic themes and inform the audience about them. Tiff’s done a good job of inviting different presenters to introduce and contextualize the films. They’ve also done a good job of giving subtitles to some of them. This is one of the problems with ‘genre’ films: they are often not subtitled. So it can be a lot of work. For example, we showed the (classic) filmQeysar at UCLA a couple of years ago.

I had one of my students translate the dialogue into English, then had another type it, and another put onto PowerPoint and finally someone to just press a button while screening the film to make sure the text appears in sync with the images. And let’s remember, part of problem is with the management of archives. I think that the Iranian government can make money by producing good copies of classic films and distributing them…Right now, when you want to get a film from Iran you have to go through a lot of red tape. And there’s the problem of the embargo: how do you pay someone in Iran? The money paid for the films here in this festival was mediated through Paris.

As you know, Jafar Panahi’s last movie received the prestigious Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. There is concern among Iranians that the award was given to him due to the political motifs of his film. Do you have any thoughts on this? How do you see the role of politics in relation to the reception of Iranian films at contemporary film festivals?

I think that politics has a lot to do with it, both negatively and positively. One the reasons that Iranian art cinema became such a global cinema is because of bad image of Iran currently. Film festivals currators are generally in favor of the underdogs; they want to show artists as individuals working against governmental pressures. On the one hand, Iranian art cinema fits this category. On the other hand, Western governments have made Iran out to be such a pariah (as has the Iranian government) that films coming from inside Iran garner a great of interest. So people wonder: ‘how do they make films in this country, this backward, medieval country?’ And suddenly a couple of films come out, and they see depictions of ordinary people concerned with everyday things. The little boy [in the film] is such a moral guy. He takes this friends notebook by mistake, and then does his homework for him so that he won’t get into trouble the next day. What a humanist! So this presents a contrast to these stereotypes, and feeds further interest in Iranian cinema. So politics is a double-edged sword. It gives an opening to cinema while politicizes it…But I think that, over time, people have learnt that you can make films that are political but that are not about ‘politics’. And most of the Iranian art cinema filmmakers are making films that are politics but not about politics as such. They are also [address] the politics of representation, and the very act of filmmaking. So suddenly the question of ‘what is a film?’ comes to the foreground in Iran. Many of today’s art cinema films in Iran are not only about the subject at hand, but also about cinema itself. Close Up and The May Lady are very good examples of this. I mean, the very first Iranian feature film made in 1933, (Haji Agha the Cinema Actor) is about cinema.

Finally, I heard that your daughter is directing a movie about you. Is this true?

No, it’s not my daughter. My daughter started asking a lot of people that I know to contribute recollections for some she was putting together for my 70th birthday. So people sent photographs and drawing and things. Someone else leads the documentary: Maryam Sepehri. Where it’ll go and what it’ll be I don’t know.