In 1885, a 20-year-old student named Sven Hedin set off from Baku with the goal of seeing Persia. He had arrived from Stockholm seven months earlier to serve as a tutor for the young son of the Nobel brothers’ chief engineer who was working in oil fields known as “the Black City.” Since childhood, Hedin had dreamt of becoming an Arctic explorer, but he happily accepted this chance to travel abroad, even if it meant a different destination. He soon fell in love with the East, spending his evenings learning to speak Persian, Russian and “Tatar” – e.g., Azeri. His favorite past time was

to go through the villages on horseback making sketches of the Tatars, their women. children and houses, or gallop into Baku on a frisky horse, there to stroll around the bazaar where Tatars, Persians, and Armenians sitting in their dark little shops sold rugs from Kurdistan and Kerman, hangings and brocades, slippers and big fur hats…. Everything was enchanting and interesting to me, the dervishes in their rags, as well as the local princes or “Beks,” in their long dark blue coats.1

When Hedin’s term of service concluded in April, he decided to spend his earnings of 300 rubles “on a horseback journey, southward through Persia, and thence down to the sea.” This fateful “road trip” would launch his lifetime career and introduce Persia to the West. 2

While Hedin eventually became best known as a geographer and explorer who mapped vast expanses of Asia, his early adventures in Persia became the basis of his first book, Memories of a Journey Through Persia, Mesopotamia and Caucasus. Of course, there had been other European travelers’ accounts about Persia, but Hedin’s vivid stories caught the public imagination intrigued by Orientalism. His lively and poetic writing style teemed with descriptions of exciting encounters, exotic locales, and ethnographic details. Hedin skillfully wove history and literary references into his narratives, providing a cultural context for his observations. While modern readers may find some of his commentary and adventures painfully Eurocentric – if not altogether disturbing – Hedin’s accounts provide a glimpse of Qajar Persia.

When Hedin departed on horseback, he traveled with the young man who had been his language tutor, but his companion fell ill and decided to return home. Hedin went on alone “but one could not be quite alone when traveling with hired horses through Persia. A groom went along, so the two horses could be returned to the station from which they were borrowed.” When he finally arrived in Tehran, he sought out a fellow Swede, Dr. Hybinnet, who “ranking as a Persian nobleman and bearing the honorable title of Khan– or prince – had been the dentist to the Shah of Persia since 1873.… Happy at meeting a compatriot, he received me with open arms and for a time I lived in his beautiful home, the decorations of which approached a Persian style. Day after day we tramped about this great city….”3

On this first trip, Hedin had none of the special equipment needed for a true expedition, but he kept detailed records and used his artistic skills to sketch various scenes and people. He later noted that,

Frequently in my journeys, I would encounter nomadic communities, camping with their black tents. Often I looked in upon them and made sketches. Once, when I asked to draw a picture of a nice-looking nomad girl, her father absolutely refused to let her pose. When questioned regarding his fears he answered, “if the Shah sees your picture, he will want her for his harem!” 4

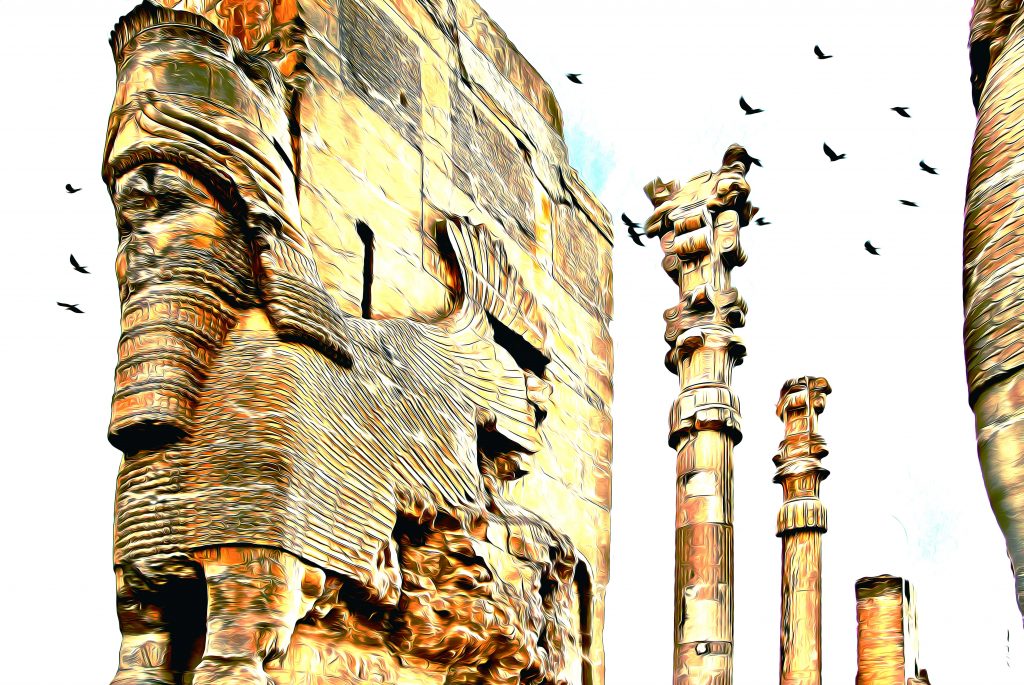

Hedin left Tehran and continued on to Shiraz, Pasargarde, Persepolis, and Bushir. He returned to Europe to study geography and geology at the universities of Upsala and Berlin. His mentor in Berlin was none other than the celebrated German geologist Ferdinand von Richthofen, the very man who coined the term Seidentstrasse, or “silk road.”

Hedin found a publisher for his first book, an account of his Persian travels, illustrated with his own sketches. The volume established the young man as an authority on Persia. In 1889, when Stockholm hosted the Congress of Orientalists, Hedin sought out “four distinguished Persians, charged by Shah Nasr-ed-Din to present a Royal decoration to King Oscar II.” For Hedin, it felt “like a breeze from home to speak with the sons of Persia and I longed to revisit their country more than ever. Aladdin’s lamp was lit anew and it burned with a clear flame.” This wish was soon fulfilled when Sweden’s king requested that Hedin accompany an official royal delegation from his court of the Persian Shah. This second trip to Persia provided a vast contrast from his initial visit:

On the day that we entered Teheran, the Oriental splendor reached its climax. How different from my first entry! Then I had come as a poor student; now I came as one of the King’s ambassadors. Whole regiments of cavalry were out in full uniform and infantry lined the street. Mounted bands played the Swedish national anthem and we were received in the garden by the high dignitaries of the country. Here we arranged our cavalcade. Arabian horses, with saddle cloths embroidered in gold and silver and panther skins under the saddles, were given to us to ride. Even the horses took fire from the music and went dancing gracefully through the city gate. The whole population seemed to be afoot to witness our entry. 5

The procession ended at the Sepah Salarresidence where the delegates would stay while in Tehran, surrounded by an impressive garden, which Hedin,noted for its “luxuriance and beauty.” For twelve days the foreign guests attended banquets and entertainments in their honor. Hedin wrote this account of their royal audience:

Photographs and illustration used with the permission of the Sven Hedin Foundation

Shah Nasr-ed-Din was in black. On his breast he wore forty-eight enormous diamonds and on each epaulet three large emeralds. On his black cap was a diamond clasp and at his side hung a saber, the sheath of which was studded with gems. He observed us fixedly. He carried himself royally, and stood there like a real Asiatic despot, conscious of his superiority and power. 6

As distinguished guests, the delegation enjoyed the opportunity to view the contents of the Shah’s personal “museum.”

Among his treasures, we saw the diamond Daria–i-nur – or the “Sea of Light” – and a golden terrestrial globe, two feet in diameter, on which the oceans were represented by closely set turquoises and the Arctic regions by diamonds, clear as crystal, and Tehran by another jewel. We also saw glass cubes entirely filled with real pearls from the Bahrain Islands, turquoise from Nishapur, and rubies from Badakhshan. 7

After the official mission of the delegation concluded, Hedin telegraphed King Oscar for permission to stay behind and continue his explorations. The Swedish ruler agreed and even promised to cover the cost his journey.

By happy coincidence, the Shah planned a summer trip to the Elburz mountains and Hedin, as Dr. Hybinnet’s guest, was invited to accompany the party. He found the undertaking both “enchanting and impressive” involving two thousand beasts of burden and twelve hundred persons. “When we encamped at night, a city of three hundred tents sprang up in the lonely valleys.” The Shah’s horses “wore red plumes; and the white ones had their tails dyed violet.” Even the Shah’s cats came along, traveling in velvet lined baskets. 8

The journey took them near the fabled Mount Damavand and Hedin decided to climb it. He approached the Shah with this request and met with approval. The young Swede set off to Rahna, where the village elder assigned to him two guides, Kerbelai Tagi and Ali, both of whom had climbed the mountain thirty times to procure sulphur. They began their ascent, but Hedin refused to pause part-way to spend the night in a cave, insisting on going farther up the mountain and forcing them all to shiver through the freezing night. Perhaps Hedin understood that a travel tale about tents and cats needed more drama so, even when stricken with the symptoms altitude sickness, he continued, eventually so weak that his guides pulled him to the summit. Hedin managed to make some sketches there and then, following the example of his guides, sat down on the snow and slid down slope for about seven thousand feet. A few days later, when summoned by the Shah to report on his climb, some courtiers questioned whether the Swede had indeed reached the summit. But when the Shah saw his drawings, “he turned to them and said: ‘Refte, refte, bala bood.’ (He has walked, he has been up there.)” 9

Hedin parted with the Shah and Dr. Hybinnet, continuing on to Russian Central Asia and Xinjiang. Other daring expeditions followed, but Hedin returned to Persia in 1906, this time at the head of his own expedition team, seeking out places seldom, if ever, frequented by Europeans. By good fortune, Hedin arrived at the oasis town of Tebbe “two days before the greatest annual festival of the Shiites in the first month of the Mohammedans lunar year, Moharrem ” commemorating “the sorrowful memory of Hussein’s martyrdom at Kerbala.” Hedin noted that “in all the towns of Persia the anniversary is celebrated with songs and plays, with loud wailing and tears.” He asked permission to attend but “as a kafir or unbeliever I could not go too near. My friend, the Governor, who fulfilled all my wishes with the greatest amiability, had at first expressed some anxiety with regard to my presence at the play. He could not answer for his countrymen’s self- control… Their fury against the enemies of religion might find in me a convenient object of attack.” The Governor ordered a strong guard to surround and protect his foreign guest who, at some distance, set up his camera to photograph the event. 10

The actual play was performed on a raised platform inside a tent; the distance was too great for Hedin to distinguish much more than shadows. He enjoyed a better view of the portion of the play that depicted the battles at Kerbela, because men and animals passed right in front of his vantage point. “There marched real caravans of camels, the finest and tallest animals that could be obtained, elegantly decorated with cloths and finery, red rosettes, ribands and tags, bells and rattles, and whole rows of boys sitting in on. them.” Hedin noticed that while women were in attendance at the passion play, they were sequestered and “only men and youths appear in religious plays and the latter take the female parts dressed in correct costumes.” There were horsemen too, in helmet and sword, along with

soldiers in ancient costumes with lances, flags, and spears with pennants attached. The performance is interesting, and is an unexpectedly brilliant scene. It is astonishing to find such great resources in this small oasis in the heart of the desert. The well-kept garden, the white tent roof, the silent palms, the motley dresses, the life and movement, the animals, all was exceedingly attractive and full of color.”11

Hedin enjoyed his time in Tebbes where he had been allowed to set up his tents in a lovely garden. His hosts brought gifts of food: “My table overflows with milk and honey, in a literal sense; we live like princes, and might imagine we were translated to Muhamed’s paradise – but without the houris, for the dark blue apparitions who skim about the streets are forbidden entrance to our garden. We are tabu, inaccessible to all eyes.”12

One of the results of this particular expedition was a series of maps of Iran and detailed geological findings. Hedin’s lifetime of exploration yielded numerous books that brought him fame. His engaging style made him a popular lecturer. relating his adventures as an explorer and his discovery of lost cities in the Taklamakan Desert. Greatly admired, awarded medals, and feted by heads of state, he became the last person raised to Swedish nobility. But Hedin’s reputation became when tarnished when, concerned about growing Russian aggression, he sided with Germany in both world wars. It may be best to remember Hedin in his early days, as that adventurous young man setting out on horseback to discover Persia.

This article originally appeared in the 2017 edition of Tirgan Magazine.

Sources

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. My Life as an Explorer.1925.

- Hedin, Sven. Overland to India. Volume 2. 1910.

- Hedin, Sven. Overland to India. Volume 2. 1910.