Shahrokh Yadegari is a composer and sound designer at the department of Theatre and Dance at the University of California, San Diego. He is participating in Tirgan 2015 where his latest play, “Scarlet Stone”, will be performed. Based on an ancient Iranian epic, this composition draws from a variety of artistic disciplines, cutting-edge technology, and some of the best-known talent in the Iranian diaspora. We thought an interview was in order, and he was kind enough to agree.

Tell us about your theatrical production of the poem Scarlet Stone (mohre-ye sorkh). What drew you to this work?

Scarlet Stone [the play] comes from my collaboration with Shahrokh Moshkin-Ghalam, a renowned Iranian dancer and good friend. We were both interested in working on a project together. We did a bit of research, and decided to take up this particular poem: the last work of [Iranian poet] Siavash Kasraei (1927-1996). I think Shahrokh and I share an appreciation for contemporary art that engages its audiences by drawing from the latest styles, but also remains true to its origins. The theme of this poem is the Iranian revolution of 1978-1979, but the issues it raises continue to resonate in present. It doesn’t deny past struggles, but it draws the audience’s attention to Iran today and the responsibilities that come with hope. Kasraei has written it in such a way that it speaks to every Iranian whose life was impacted by this revolution. In my reading, art can’t easily separate itself from political and social issues, and yet its work must also stand apart from them. Shahrokh and I were looking for a story that could engage with Iran’s recent history without being too overtly political. In Scarlet Stone, Siavish Kasraei demonstrates deep insight into both Iran’s past and his own. We hope this work provokes personal reflection and dialogue amongst its audience. The entire poem will be translated into English during the performance, and so it’ll engage both English and Persian-speaking audiences.

You began pursuing a career in music following your education in electrical engineering. What drew you to music in the first place? And to what extent has your scientific background informed your work as a composer?

Music has always been a big part of my life. After graduating from engineering, I felt that something was lacking. At that time, I began seriously pursuing an education in Iranian traditional music and researching modern Western music. In 1988, I had a chance to research electronic music in Paris at the IRCAM (Institut de Recherché Coordination Acoustique/Musique); established by famous French composer, Pierre Boulez. This experience had a real effect on my interest in music, and was perhaps a turning point as I decided to commit my professional life to artistic content rather than analysis of technique. I’ve worked more on these two musical genres in the past few years. But it took several years before I reconciled them; my sense of Iranian music and my knowledge of electronic music. I didn’t want to force it. I think that this combination of traditional and electronic music should offer new lessons, while retaining the original elements of each. My scientific and technical background enabled me to create a new language in Iranian music to express my musical feelings.

Scarlet Stone crosses paths with the classical epic The Book of Kings (Shahnameh) by Ferdowsi (a major Iranian poet; 935–1025 CE), and yet retains its own narrative. Where do they meet?

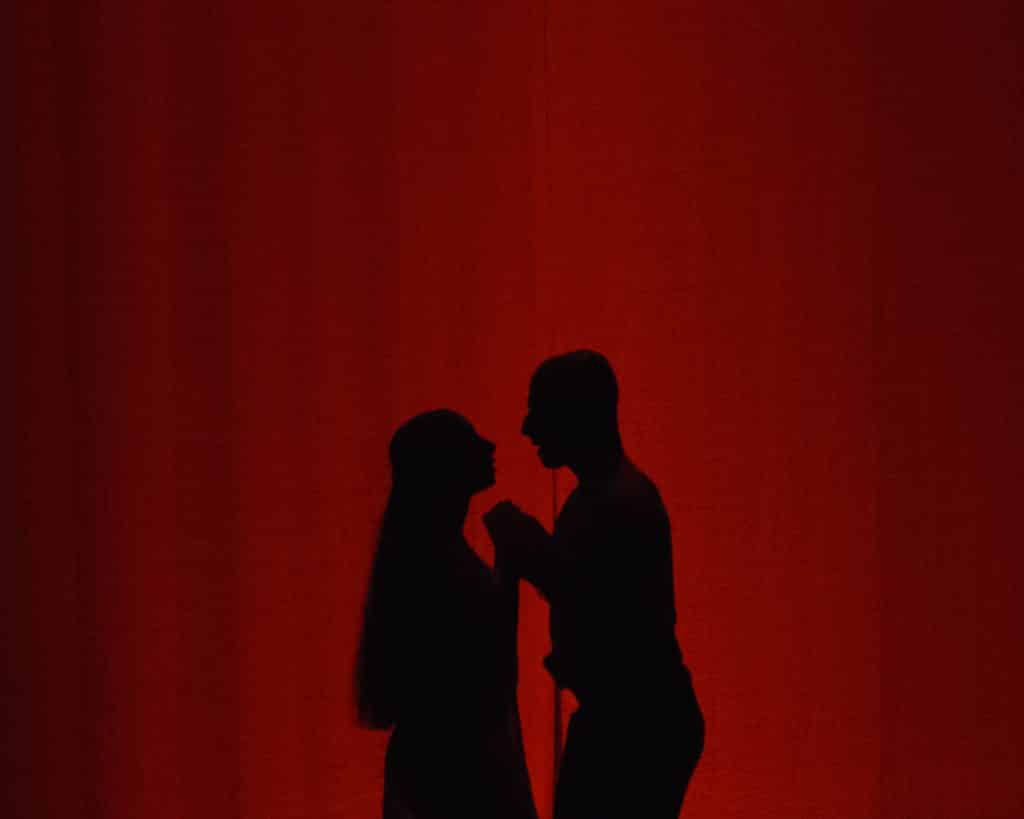

The poem Scarlet Stone is based on the most popular story from the classical epic The Book of Kings: the [father and son] story of Rostam and Sohrab. Kasraei wrote a modern rendition of this old mythology. The combination of new and old approaches and ideas informs all the key elements of the play; in its text, dance, choreography, music, staging, and costume design. The play begins with a scene from The Book of Kings, the meeting of Rostam and [his wife] Tahmine. By the time that Sohrab [his son] lays dying, the play brings the audience to Kasraei’s poem. Sohrab is symbolizes the new generation. He goes on to reflect on his life, his relationships as he searches for answer to his past and his remaining fate.

A lot of cutting edge staging technology and techniques have gone into this play. What is the idea here? Is it to offer us a new twist on an old tale?

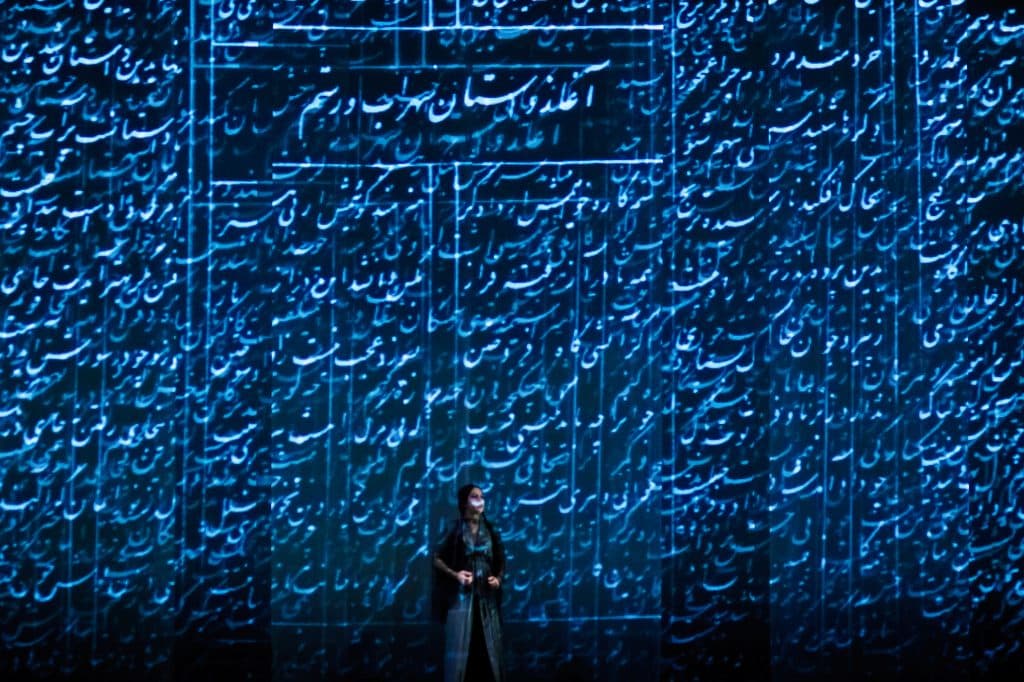

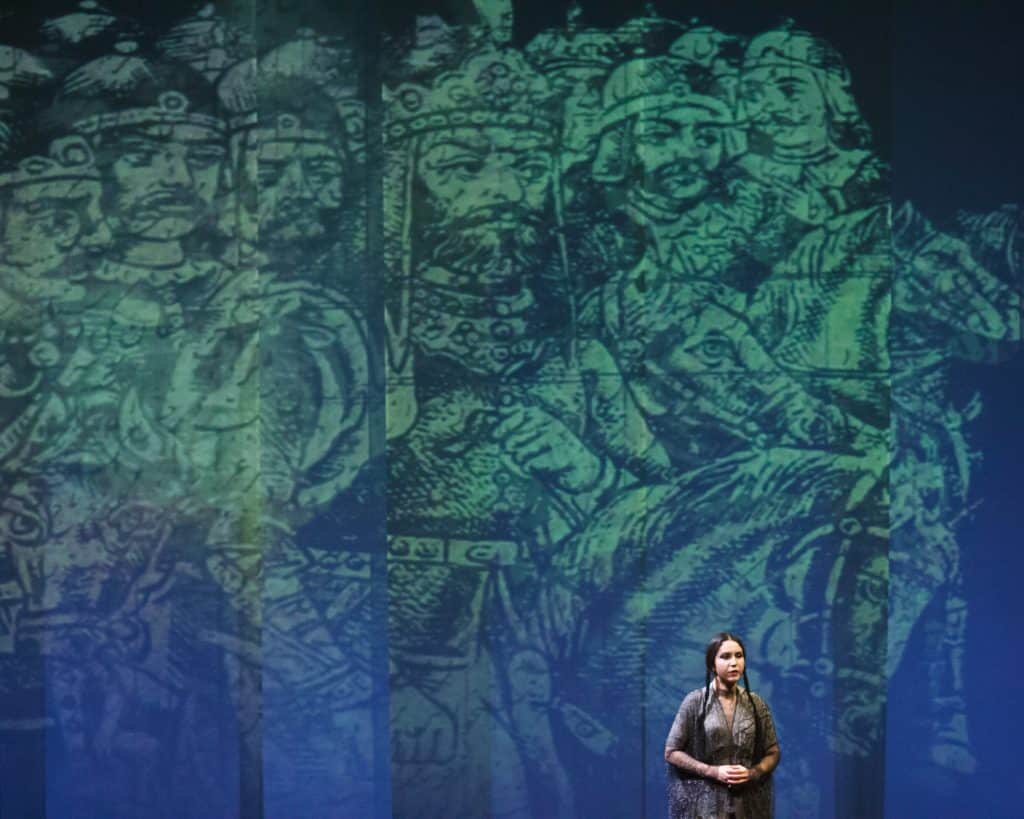

I can honestly say that the fusion of old and new runs through the entire play. Just as Siavash Kasraei’s poem, the Scarlet Stone is a modern rendition of an old epic, the staging, music and choreography are a modern homage to an the ancient art. The play draws from elements of the old theatrical styles of “curtain reading”, and the narration of epics. But it does so while using current staging technologies. Interactive projections (designed by Ian Wallace) have been key to pulling this off. In the traditional style of narrating epics, the narrator relied on a static image and pointed to the events in the story it depicted. In Scarlet Stone, these images are constantly changing as they follow the narrator’s performance. A computer registers the power and tone of the narrator’s voice and controls the change and color of the projected imagery. The idea here is to use such technology to better convey the story’s emotion and meaning.

About your choice of music, why rely on percussion instruments? How does it resonate with the words and the rest of the performance?

The use of percussion—and especially those of the zoorkhane (the arena of a traditional style of Iranian martial art) is commonly used for the narration of epics, but in this project percussion has been used to create the same atmosphere. For scenes of battle, rhythm is used to express delight, risk, uncertainty, and also helps create energy. Rostam and Sohrab battle twice in two different ways. First we see Sohrab’s struggle through his thoughts, feelings and sense of distress, without Rostam. The second time we see their physical duel. The Rhythm in the first one is more stable, and the melody stronger as it is accompanied with electronic beats: here is frenzy, passion and Sohrab’s youth. In the second battle, the rhythm begins gently and gradually builds into a powerful martial rhythm that envelope the theatre.

The play relies on a variety of different artistic styles and performers. How did you coordinate them to pull off this adaptation of a historical Iranian epic?

I can say with certainty that it was the result of shared commitment and generosity. The role of each artist is associated with his or her character. Ms. Gordafarid was chosen to play the role of Ferdowsi deliberately. But her coming to San Diego just as we got ready for the phase of rehearsals was unexpected. It was with her help that we rendered the adaptation and drafted it. After having retired from ballet for several years, Afshin Mofid came back to the stage for this production. It was the draw of playing Rostam: the role that reminded him of his grandfather, Gholamhossein Mofid, who also used to play it. Ida Saki performs the role of Gordafarid—a strong and intelligent woman—with much poise. Her character has captivated whoever is familiar with her art, or may know her personally, and art (much as Sohrab is captivated with Gordafarid). Ms. Miriam Peretz elegantly plays the role of Tahmine, and though she isn’t Iranian she is intimately familiar with Iranian dance and artistic culture. While I was composing for the play, I was trying very hard to ensure that the music would create a meaningful atmosphere for the narration of this epic, and the dancing choreography of Shahrokh Moshkin Ghalam. Likewise, Shahrokh tried to coordinate his performance with the talent around him.

Tell us about your experience in performing or producing compositions for non-Iranian audiences. To what extent have you found such audiences to be familiar with Iranian narratives or artistic traditions? And does this have any bearing on your artistic approach?

Non-Iranian audiences may find Scarlet Stone interesting as it introduces them to Iranian mythology and also the 1978-79 revolution. That’s why it features a translation that follows along with the play. Siavash and Eva Nemat-Naser have done a great job of ensuring that these translations are understandable. It also needs to be said that a lot of non-Iranian viewers who have attended our previous programs said that they could just listen to the play as a musical performance because it’s a poem after all. We’ve tried connecting both emotionally and intellectually with the audience—Iranian or not—by weaving together several arts: theatre, music, dance, poetry and animation. Our efforts at translation have received a lot of praise from non-Iranian viewers. When I decided to perform the play with the full translation of the poem, I was sure that it would connect with a non-Iranian audience. But [even] I didn’t expect it to engage them to this extent. The performance of this play and reactions from non-Iranian audiences has proved to me that many traditional and modern Iranian arts are cosmopolitan and universal in their appeal.

Translation by Samane Tavassoli

Googoosh