In pieces of Greek art of different kinds we can see authentic Persians depictions and supposed “stylized Barbarians” images in scenes from Greek myths and the Trojan epic poems, mythical Amazones in”oriental” costume and“Barbarian hunting”. But it was not easy: the most part of such costume depictions of powerful enemies of Greece-Persians were the trustworthy or the presented ones are a rather inexact stylization, a sort of a symbol of Others, of “Barbarian”motley and alien luxury.

Really we have a big series of authentic depictions made by Persians themselves or to their order. Besides, Greek and Roman authors preserved a lot of written witnesses of the costume of Achaemenids and their Persian subordinates. Among outstanding Greek depictions of the end of the 4th c. BCE, which show the clothes of Persian warriors so on after the Achaemenid Empire fall with ethnological exactness,two objects are famous: a prototype of a Roman mosaic from Pompeii with the scene of Alexander the Great and Darius III meeting in the battle by Issus in October 333 BCE and the so-called marble “Alexander’s sarcophagus” from Sidon. Probably, both monuments go back to the canvas by Philoxenos from Eretria ca.317 BCE.

Dr. Wolfgang PFÄFFL [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Alexander fighting Darius – Museum of Napels, Mosaik in Pompei

Comparison of these reliable evidences and the images of Imperial art with Greek depictions of mythological characters in“oriental” costume makes possible to see authentic features of Persian costume in most cases (it concerns Amazons in a smaller degree, even many Amazons look as authentic men-Persians. This authenticity may be explained by some very different reasons. It was often the results of political actuality, military and political power of Achaemenids (for example, the inhabitants of Panticapaeon in the far Bosporan Kingdom in Crimea evidently ordered depictions of real Persian kings–Cyrus the Great, Darius I and Abrakom satrap of Syria and others to the Athenian vase-painter Xenophantos). Apart of Greece and its colonies were under Achaemenids authority. Due to the fact that the Persians were a symbol of the “Barbarian World” in illustrations of various Geek myths all “Barbarians”often look as the real Persians. Also a great number of captive Persians were in Greece (in many situations the slaves used their national costume). And after first war victories of the Greek and thirst for forbidden and censured oriental luxury and comfort the in some situations, the fashion for Persian clothes appeared.

While Persian masters concentrated on the costume of “king of kings’, wives from the harem, courtiers and priests, on authentic depicting of silhouette and accessories as status signs, Greek artists were more interested in less socially significant personages and made the main accent on cloth décor in upper body garment (a sarapis shirt, more seldom a kandys), trousers-anaxirydes and cloth draping in a tyara headdress(2:3). Unfortunately, the authentic Persian textiles with their ornaments are not numerous. Greeks could see such costume complex in battles and everyday life of warriors from Persian garrisons. Depicting Persians in such kind of costume became a certain stereotype. Such costume, as it has been mentioned above, is presented quite authentically, but unvarying and unaccomplished; nevertheless, later Roman depictions of Parthians, for example, present their looks even less informative and more standard. The fact that in Attic art some authentic elements of Persian costume are given with mistakes and a certain degree of stylization are not the main things.

Persian costume in such depictions is rather unvarying and presents only few of a great number of ones known today elements of Persian male costume in Achaemenid time. For example, in Greek art only one type of headdress –a tyara, of nine types defined by me for Persians is constantly depicted and is of a stereotype character! A saparisis a dominating type of upper body garments. A gala kandys worn above it is usually behind the back, fastened with a pin (as Persians really wore it like this during the battle and while hunting); the trimming of lapels made of fur or expensive fabrics is not accentuated at that. A sleeveless clock-kasis depicted more often than in Persian art. On the contrary, a wrapped from the right to the left gaunaka caftan is practically not pictured by Greeks whereas leggings, well-known for Persians, are not presented at all. The decor of fabrics for trousers-anaxirydes is usually of one type (horizontal zigzag lines), really popular in Persian everyday life.

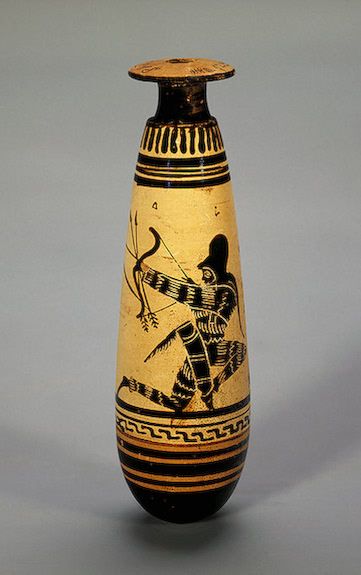

The correlation between figure and clothing of Persian personages is seen differently by Greek and Persian artists. Iranian depictions usually show such clothes loose. In Attic vase painting ethnical Persians, even in case of protocol exactness, give the material with a certain part of conventionality and exaggeration due to the dominating style. Therefore, trousers and the upper part of a sarapis are usually depicted close-fitting the body like modern sport suits (however, anaxirydes were really very tight: Xen. Cyr. VIII. 3. 13). Greek artists often accentuated a vertical decorative line on a sarapies, which in official art of Achaemenids was not considered necessary to be underlined and sometimes they also emphasized on a decorative line along the collar neck cut. Some single details are often exaggerated. For example, a sharp protruded element of the back part of a tyara headdress in an alabastron from the Hermitage Museum (ca. 470 BCE) has extremely prolonged and thick lower juts.

From time to time we deal with some single inexactitudes. Depictions of “stylized Barbarians” in garments combining costume elements of two different peoples (the Persians and the Scythians, the Persians and the Greeks) are rather frequent. Sometimes a Persian personage is presented in Greek high boots, which could not have been possible in reality.

There is a very valuable king’s depiction in the so-called “Crater of Darius” or “Vase of Persians” (the middle or the end of the 4thc. BCE; 1,15m high with four tiers of painting) from the National Archaeological Museum in Naples. Here, Darius on the throne among his councilors is listening to a traveler standing in front of him. The authenticity of the king’s Persian costume was earlier denied by A. Gow. Admittedly, the king’s hair is too long; the complex pattern of plant scrolls of the red tyara has no Persian analogies; but there are such interesting details as triangular elements of the lower front edge of trousers legs and fixing of trousers legs with bracelets a little higher, which has distinctive authentic parallels with Scythian and Chorasmian costume of that time, and, probably, Persian one.Sometimes Darius looks like a simple Persian officer

A young Persian warrior from the west pediment of Aphaia Temple in Aegina Island (ca.490-480 BCE) in the scene from the Second Trojan War (München Glyptotek) wears a garment of authentic Persian silhouette; we see an ornamented trimming even on the leather armor worn above a sarapis shirt. On the whole, the statue reproduces small details of motley fabrics ornament rather exactly. We can see the similar décor not only on the trousers of some Persians from “Alexander sarcophagus”, but on Persian depictions from Persepolis. Horizontal many-colored zigzag lines are the basis of this ornament. The tyara headdress which is fixed with a wide band above the forehead presents a certain interest. Practically, there were no Persian male personages shown from the back, therefore,the above-mentioned sculpture is very valuable due to a vertical line of many-colored décor on the back which has analogies in Scythian costume of that time. Two palmettos in the upper part of the tyara can be considered the only violation of a Greek master.

The image of a fair-haired warrior (according to another version –“a dancing Barbarian”) on a rare (as far as its shape is concerned) sculptural vessel (4thc. BCE) which was discovered in Pavlov Barrow near ancient Panticapaeon (in the Hermitage Museum), is traditionally referred to as a “stylized Barbarian”. But I cannot see serious grounds for that. The young warrior holding up a weapon (?) in his hands wears a kandys fastened at the collar on the back, shoes, tight trousers, a black tyara with a red lining and long bands for fastening from the sides. His sarapis shirt (with a vertical line of décor, known in many Greek depictions of Persians) is lowered a little and tied around his tights, which, probably, was the manner to wear it typical for Persians. The unfrequented green color of the shirt and the white color of the shoes are also presented in images of Persians in the mosaic from Pompeii; small gold ornaments fixed in the hair being the only non-authentic detail.

The fact that Greek vase painters and sculptors did not depict even noble Persians in gala complexes of clothing and accessories (partly borrowed from Media and Elam–a large pelerine-kapyris, a long skirt, a crown with a row of sharp teeth, a “rewarding” diadem, artificial curling of hair, gold accessories –pectorals, torques, necklaces etc.) is very important. The knowledge of Greeks –mercenaries and political emigrants –about Persian gala costume and its depictions on trophies, coins was not reflected in Greek art. It can be mostly explained by the character of plots (usually mythological): different “Barbarian”rulers and their subordinates mentioned in them had a Persian look. Nevertheless, even in throne scenes we see Persian kings and satraps not in their ceremonial gala costume but in more practical, adjusted to war and hunting garments which were repeatedly described by Greek authors (such costume differs from the analogous one of less noble warriors only due to a more exotic ornamentation).